The Direction of Democracy is Direct Democracy

The Politics of Economics is a Ponzi Scheme

Hello everyone, you may not know me, especially if you do, please read this as an attempt to help, not harm. Put on your favorite song, take a walk, step outside and engage the world — anything that reminds you that you have power, you can make a difference.

I asked Dr. Susan Calvin (AKA my ChatGPT assistant) what a Ponzi scheme is, as my goal in this post is to explore why we can never seem to achieve a balanced budget in America that brings down debt. But before we get there, let’s take a step back and examine the history of our economy in what I humbly hope is in an approachable way.

This is going to take some time to break down, but stay with me — this history is crucial to understanding why economic policy should be put back into the hands of the people. After all, it’s our money and our debt.

I would also ask that folks try not to fall into the perpetual mode of “He’s not an economist” or “He’s just an X, Y, Z” echo chamber of “Policy X, Y, Z.” I am a real person, not a professional writer, not a celebrity, not funded nor asking to be funded by any political force. On the contrary, I am biased against rhetoric, have a reasonable vocabulary and I can do math. And the math doesn’t add up.

Elevating The Case for Public Control Over the Economy

U.S. history has shown us that those in power are incapable of crafting adequate policy for the time. Instead, they remain locked in a war of attrition over political control of the economy — when a vote by the people could, perhaps, allow us all to be accountable for our future.

The Only Time the U.S. Had “Zero” National Debt

In 1835, more than one hundred and eighty years ago, the federal government completely paid off the national debt and this is the only time this has ever happened. Congress maintained a balanced budget briefly, relying on strict fiscal policies and high tariff revenues.

Unlike today, tariffs were the government’s main source of income, as there was no federal income tax (the 16th Amendment wasn’t passed until 1913).

Congress and The President in this time made several controversial choices to reduce national debt, including eliminating infrastructure projects and imposing tariffs in the absence of an income tax. Adjusted for 2025 dollars, the national debt at the time was about $1.2 million.

Comparatively, the national debt per person was negligible. Even with an average person making no more than $500 per year, the debt per person was as close as I can find about $0.09.

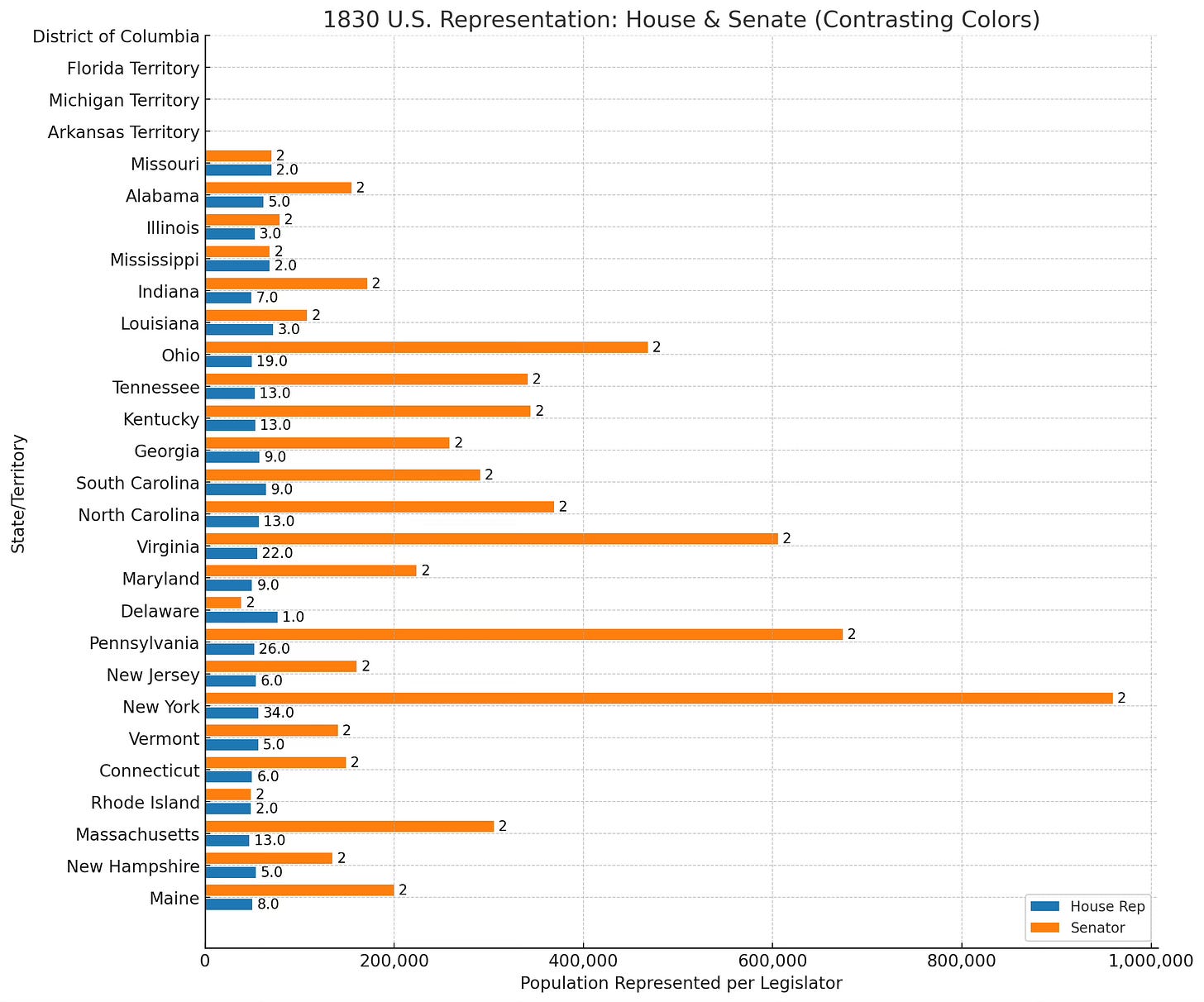

In 1830, the population of the United States was approximately 12.8 million, which included an enslaved population of approximately 2.3 million and an autonomous population of approximately 10.5 million.

Each member of the House of Representatives represented an average of approximately 60,000 people, however this varied significantly by state due to the Three-Fifths Compromise, which artificially increased representation for states with large enslaved populations who had no voice, or choice.

Meanwhile, the Senate’s structure created even greater disparities as each state — regardless of population — had two Senators, meaning that in New York (population approx. 1.92 million), two people represented nearly a million residents each, while in Delaware (population approx. 76,748), two Senators represented fewer people than a single House Representative from a larger state.

The imbalance in representation across both chambers highlights a crucial issue in our constitution. No state or territory truly has proportional representation for its entire population.

Addressing Andrew Jackson’s Legacy

Now, I need to make one thing clear: I am not evangelizing these policies, the time, nor the presidency of Andrew Jackson. My personal opinion? Jackson was a petty king who abused power. He ignored Supreme Court rulings, rewarded loyalists and set the stage for the modern political power struggles we see today. If there’s a root cause of executive overreach, he’s it.

Also, this is why I would have challenged him to a duel for the honor of my country:

In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court ruled against Georgia, affirming that Native American tribes had sovereign rights.

Now, everything in real life is far more complicated than just a quote and you should read this wikipedia article on the case, but Jackson as a politician did not take the matter further as a matter of political appeasement. The aftermath was that Georgia’s government (where I now live) forcibly removed the Cherokee Nation from Georgia in a “treaty“ they signed. I am quite sure they had no choice but to sign. Also read and reflect on Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta in where Worcester v. Georgia is still relevant today.

I have Sweet Fanny Anne to give about any support of this. It was wrong then and it’s still wrong today. Full stop.

Part of this wikipedia article states that in 2000, Justice Stephen Breyer remarked that the Supreme Court was an “obvious winner” in Worcester v. Georgia once its judgment was issued, but the Cherokee Nation was the “obvious loser” because the ruling ultimately did nothing to protect them.

No, Justice Breyer, the Court did not “win” anything. It lost — because a ruling without enforcement is nothing more than words on paper. Politicians will not act unless they are compelled to, and in this case as with most, they were not compelled to do a thing and bravado begets bayonets. The Supreme Court, while issuing a judgment in favor of the Cherokee, provided no measure of accountability to the people or an enforcement mechanism, allowing Andrew Jackson and the government of Georgia to ignore it entirely. Welcome to 1830 and now.

I say this to elucidate the fundamental flaw in how our system of checks and balances works (amongst others) — a judgment without teeth is as good as no judgment at all. The executive branch holds the sword, and when it refuses to wield it in defense of the law with a strong civic compass, the judiciary is left issuing empty proclamations.

This case remains one of the clearest examples of how the balance of power in the U.S. government can fail when one branch simply refuses to act. Sound familiar?

That said, it pains me to acknowledge one argument in Jackson’s favor: he was “attempting” to keep banking out of the hands of the elite. While I personally find this claim scatological in nature to the merits of the intention, I can see merit in the concept of giving people more control over economics — through a modern system of national referendums and direct democracy.

Presidential Power and Economic Control

What gives a president — or any president — the right to make these sweeping decisions?

The Constitution.

In my opinion, representational democracy needs new checks and balances, reinforced by the people. The mandate of government should be to bring honorable, honest and approachable legislation back to the people, so we can decide our own liberties in concert with the legislature, not to be conducted to without a voice.

From the 1830s until now, this has not been possible. But I believe the next step in American democracy is direct democracy. We are at a point where we can restructure our Constitution to give people more say in economic policy and more.

Twentieth Century “Balanced“ Budgets

Once again a small public service announcement on my part, please accept that in referencing history, I am not promoting the policy or the people — just speaking about how our legislature has come to pass and how it affects us.

1920s and 1930s after World War One

Spending cuts after World War I.

High tariff revenues (Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act of 1922).

Economic growth during the “Roaring Twenties.”

Reduction in national debt from wartime borrowing.

I highly suggest that folks read about The Fordney-McCumber Tariffs as it juxtaposes today and is a glaring example of how history repeats itself. Also, remember that this was a time of major deregulation and a hands-off approach by government.

There is also the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930) which raised tariffs to unprecedented high levels, triggering global trade retaliation and worsening the depression we were already in. Lastly, investigate the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to understand how some of the response was in Hoover’s administration. It can be very helpful to understand some of the differences between Keynesian and Neo-classical economics and why they have been predominant in twentieth century politics. This time is really what started it all.

Post World War Two

Military spending cuts after World War II.

Strong economic growth as soldiers returned to the workforce.

Increased tax revenues from post-war economic expansion.

The Revenue Act of 1948 which reduced individual taxes.

Foreign Assistance Act of 1948 which turned America into a manufacturing giant.

Limited Social Spending as the Fair Deal proposals were blocked by congress.

I highly suggest folks read the fair deal proposals to understand how almost one hundred years ago many political arguments today are rooted in the past.

Eisenhower Surplus

Conservative fiscal policy – Eisenhower kept military spending in check despite Cold War pressures.

Strong post-war economic expansion. Consumer spending was high.

Higher tax revenues and corporate profits. These high tax rates had been in place since the 1940s to pay for World War II and the Korean War.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 created the Interstate Highway system we use today.

I want to be very clear: the $25 billion cost of the Interstate Highway System is equivalent to $315.6 billion today and was funded by a gas tax.

However, while it revolutionized transportation and economic growth, its construction devastated minority and low-income urban communities, many of whom had no political power to resist. This is yet another reason I support national referendums in our modern time and direct democracy — because in any era, accountability for a law is just as important as the law itself.

The 1990s Budget Surplus?

In the 1990s, the U.S. had a budget surplus. This proves that a balanced budget was possible in the late twentieth century under certain conditions:

Strong economic growth

Spending restraint

Sufficient revenue

However, there is a massive flaw with how the policies of the 1990s (and beyond) shaped our economy. Here are some thoughts:

Shift to a service economy: Manufacturing jobs declined due to globalization and trade agreements, leading to lower-wage service jobs replacing stable manufacturing work. This is a fact.

Lack of workforce retraining: Many displaced workers weren’t allowed opportunities to viable cost effective educational paths into higher-paying, in-demand fields, leaving them stuck in low-wage jobs.

The budget surplus was temporary: The 1990s surplus relied heavily on the dot-com boom and capital gains taxes, and quickly vanished after 2001.

Rising household debt: Wages stagnated and the economy relied and still relies on credit (mortgages, student loans, credit cards) to sustain consumer spending.

Technology became the new factory work: Automation and digital services became the new economic drivers, benefiting skilled workers but leaving others behind. Even today, technology is becoming a gilded cage creating in my opinion a massive labor force inequality based on educational elitism over vocational study and apprenticeship into math and science fields.

On top of that, debt has continued to skyrocket, driven by the constant battle lines drawn between Keynesian and Neo-classical economic policies — each applied selectively, yet neither fully solving the problem. As of today, the national debt exceeds $100,000 per person, and this trajectory remains unchanged regardless of which party holds office or who we vote into power.

This is a problem that neither 19th-century nor 20th-century economic models can resolve, as both have become unchecked fission reactors, melting down within the depths of modern political power struggles instead of serving as true solutions. There is very little in the way of moderation of economic forces, nor a control system capable of regulating its coefficients in a way that ensures stability and safety.

In my humble opinion, failure in business is one thing, failing the American economy is another.

State Sovereignty vs. Federal Overreach

There is a fine line between states’ rights and national sovereignty, and maintaining that balance is crucial. However, the phrase “The Federal Government Overreached” or “How do we pay for it?“ is often just a political dodge, used to sidestep the real issue rather than confront it.

Conversely, when the federal government does act, its response is often erroneous, failing to address the problem at its root. Gotta love it when everyone keeps over-reacting or under reacting in a cooperative way because… reasons.

The prescient question should not be who holds the power, but rather how power is wielded and to what end. The tension between state and federal authority is as old as the republic itself, and without clear accountability to the people, it will remain an eternal struggle that drives advertising revenues and market forces rather than solving problems for every day Americans as a whole.

The Argument of a Ponzi Scheme

At its core, our political economy operates much like a Ponzi scheme — sustained not by true fiscal responsibility but by the constant infusion of new money, borrowed against the future.

Keynesian policies justify deficit spending in the name of growth, while Neoclassical policies presume markets will correct themselves — yet neither confronts the long-term consequences.

Just as a Ponzi scheme requires an ever-expanding base of new investors to prop up unsustainable payouts, our government relies on tax breaks, debt, inflation, and economic expansion to delay the reckoning.

Social programs, military spending and the promise that tax cuts stimulate the economy are all founded on promises that future growth will cover today’s bills — yet the debt never truly decreases, only compounds.

All while blundering politics disproportionately burden the most vulnerable — the young striving for opportunity, the elderly who have given their years to society, working families caught in economic uncertainty, and service members who have sacrificed for a nation that too often forgets them after their service has concluded.

These failures lead not only to financial instability but, in the worst cases, to homelessness, despair, and loss of life for those least equipped to bear the consequences.

Eventually, as with all unsustainable financial structures, there comes a moment when there are more liabilities than assets, more debt than production, and more empty political promises than real economic solutions. That moment may or may not be today, but without meaningful reform, it is only a matter of time.

And, there is a meaningful argument that time has already run out.

The Future of Economic Democracy

Direct democracy can restore accountability by giving people a direct voice in economic policies that shape their lives. History shows that balanced budgets are possible, but only under specific conditions. Modern economics and political policy are failing to keep pace with the demands of our society, burdened by the unresolved shortcomings of twentieth-century strategies. Without meaningful reform, we are destined to repeat the same cycle of debt, partisanship, and economic instability.

If we are truly to move forward, we must ask: Is it time for the people — not just politicians — to decide the fate of our economy?

Before you overthink implementing direct democracy, ask yourself: is it better to act on what almost 200 million registered voters decide, rather than those who hold power over us and submit to what a fraction of the population decides?

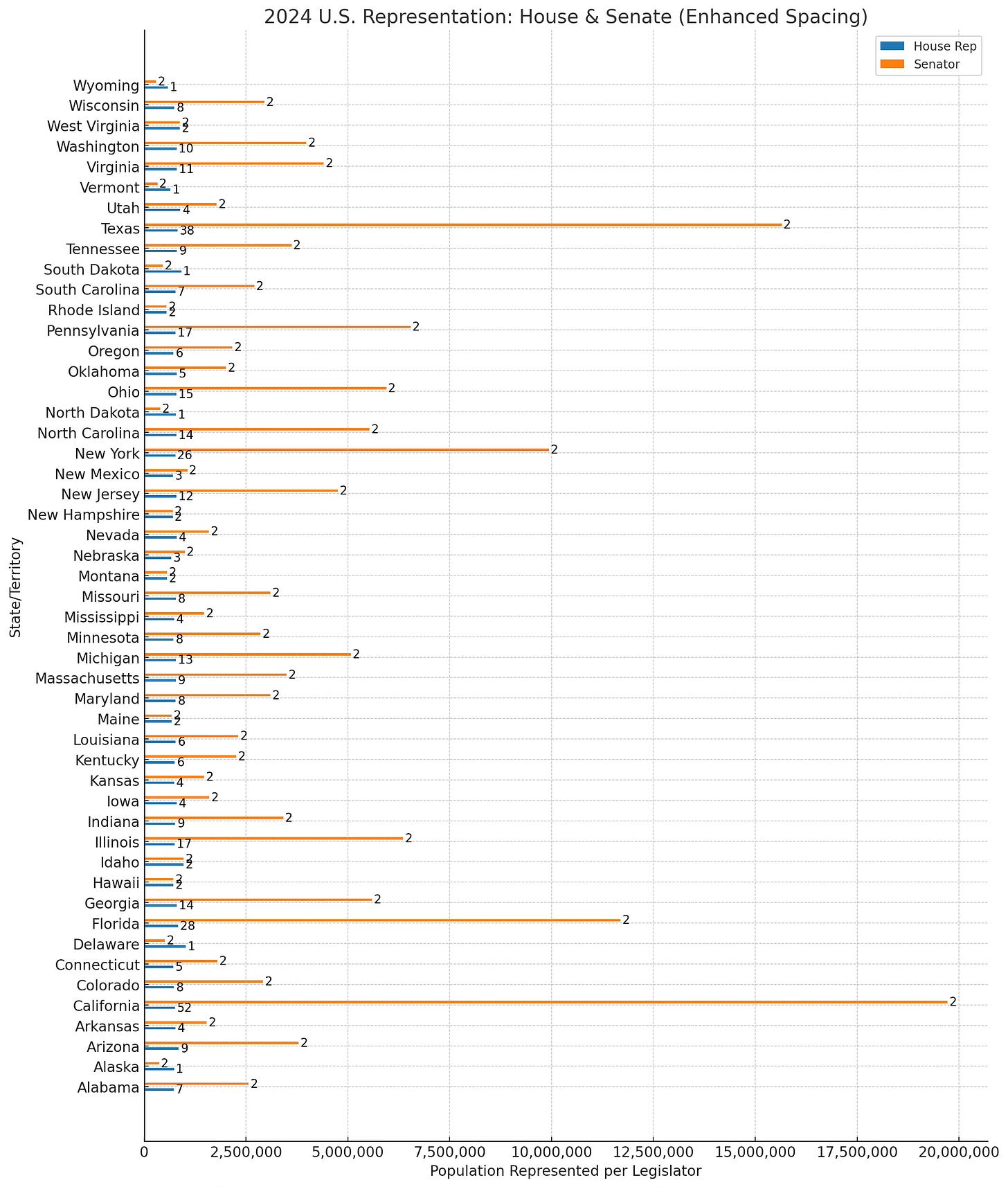

In 2025, each member of the U.S. House of Representatives is responsible for approximately 770,000 people and around 386,000 registered voters. Meanwhile, each U.S. Senator represents an average of 3.35 million people and 1.68 million registered voters in their state.

How can 535 individuals in Congress, merely one per hundreds of thousands, or even millions of us truly represent the diverse voices, needs, and priorities of the American people? The math does not add up, regardless of which state one resides.

In the constitutional convention of 1787, Benjamin Franklin was asked reportedly by Elizabeth Powel who queried: “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” As Benjamin Franklin wisely advised "A republic, if you can keep it."

The question remains: Can we keep it or has it already been taken from us?

If you have a moment, please read these two related articles. This is how I am trying to reach people in a more actionable and positive way.

Don’t code tired!